How Many Acres Is Required to Raise a Pound of Beef

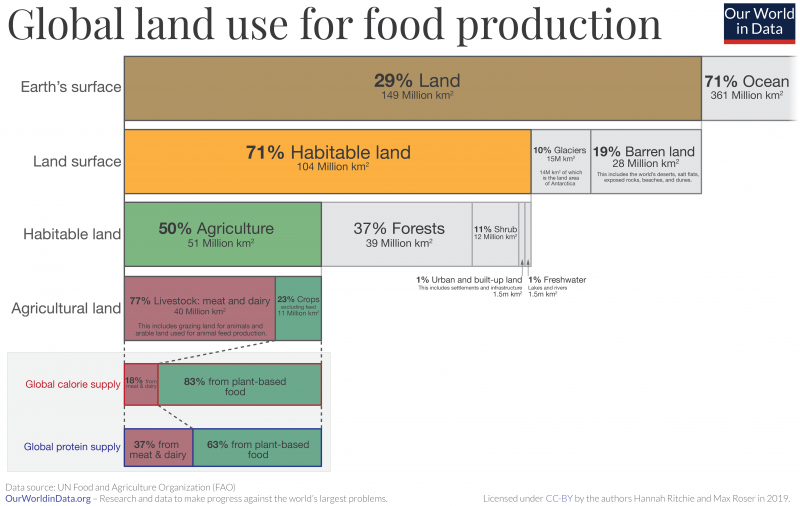

Livestock takes up nearly 80% of global agricultural land, yet produces less than 20% of the world'southward supply of calories (equally shown in the visualization). This ways that what we eat is more than important than how much nosotros swallow in determining the amount of state required to produce our food. As we get richer, our diets tend to diversify and per capita meat consumption rises; economic development unfortunately exerts an increasing impact on country resources. If we want per capita meat consumption to be able to rise sustainably at lower incomes, per capita meat consumption at high incomes will take to decrease.

This raises an interesting question: if we were to achieve a level of sustainable dietary equitability at a global level, what would our diet have to look like? Alexander et al. (2016) attempted to answer this question using a thought experiment, termed the 'Half alphabetize' (short for 'Homo Appropriation of Country for Food').1

The Half index asks and answers the hypothetical question: if everyone in the world adopted the boilerplate diet of state 'x', what percent of the global land area would we demand for agriculture?

Alexander et al. (2016) calculate this alphabetize based on the combination of Un Food and Agricultural Arrangement (FAO) national consumption patterns and global average yield and land use intensities for different food bolt. This data is based on FAO data from 2011—the latest year available at the fourth dimension of the paper'south publication. By combining metrics of dietary limerick (for example, the average per capita consumption of beefiness in the United Kingdom) and the land intensity of beef production (the amount of country required to produce a kilogram of beef based on average global figures), the authors calculated the average corporeality of land required to supply the diet of an individual in any given country. Notation that this measure does non include fish and other seafood products. By multiplying this land requirement per person by the global population, we tin make an guess of the total area (and therefore the share of land area) which would exist required if everyone in the world adopted the dietary habits of whatsoever given land. The authors define this measure (the share of land area required for agronomics if everyone adopted the diet of state 'x'), the HALF index.

We have utilized the figures from the HALF index as reported in this paper for the visualizations in this article, with one notable change. Whilst Alexander et al. written report this alphabetize as the percentage of total global land expanse, we discover it easier to interpret these figures as the percentage of total global habitable country surface area. With our change, an index value of 100 percent indicates that the global adoption of a given nutrition would be physically achievable if we usedall habitable land area for agriculture and values greater than 100 percent are not feasible within global state constraints. Nosotros take therefore adapted Half index figures for habitable land area based on the assumption that 71 percent of global total land area is habitable, as shown in the chart.

Land requirements by national diets

Today, the earth population uses approximately 50 percent of total habitable land for agriculture.

How much of our habitable land would we demand if the global population were to prefer the average diet of whatsoever given state? The results are presented in the map shown here. We accept color-coded the map based on our current agricultural land requirements and our physical land constraints as follows:

- Countries shown in blue have an average diet which, if adopted globally, would consequence in less land use for agronomics than current levels (i.e. their Half index is less than 50 percentage).

- Countries shown in yellow have an boilerplate diet which, if adopted globally, would crave an expansion of agronomical land from our current allocation, only would be physically viable within global country constraints (i.e. their HALF index is betwixt 50 and 100 percent).

- Those shown in orange accept dietary requirements which would not be feasible at a global scale, even if we converted all habitable land to agriculture (i.eastward. their HALF index is greater than 100 percent).

You lot tin explore the exact percentage values by hovering over any country in the interactive map.

Overall, there is a 14-fold difference in country requirements across national diets. If we were to achieve equitable diets using less land than we currently exercise, we tin meet that the world would have to converge towards the dietary compositions of countries across South asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and some Latin American countries (i.eastward. the countries shown in green). The largest sub-gear up of countries fall inside the middle bracket: global adoption of such diets would require agricultural expansion, merely may be physically viable inside habitable land resources. However, at that place are also a number of countries which fall into the orangish category: it would be ecologically impossible for everyone to eat the diet in Due north America, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, New Zealand, and several countries across Europe.

If everyone were to adopt the boilerplate diet of the United States, we would need to convert all of our habitable state to agriculture, and nosotros'd still be 38 percentage curt. For a New Zealand nutrition, nosotros'd need almost twice as much habitable land every bit we accept.

The link between dietary pressures and prosperity

Why are there such variations in dietary land requirements across the world? In the chart here we have plotted each country's HALF index (as represented in the map higher up) on the y-axis, against its gdp (Gross domestic product) per capita, on the x-centrality. Overall we meet that richer populations have larger dietary state requirements. Likewise shown on this graph is the proportion of state we currently apply for agricultural production, plotted as a grey horizontal line at 50 percent. The majority of countries which lie below this line are in Africa (in blue) and Asia (in cherry-red), and well-nigh take per capita incomes of less than $10,000 per yr.

The implication is that there is an of import trade-off between environmental touch on and diet: for a multifariousness of ecological reasons, including biodiversity and climatic change, we want to reduce our agronomical land pressures; just we too want a healthy and adequately nourished population. Theoretically, if nosotros wanted to restore natural ecosystems by using only 13 percent of habitable land for agriculture, we could all adopt the average diet in Liberia or Mozambique. Still, such diets are typically depression in diversity, and result in severe levels of micronutrient deficiency and malnourishment (Republic of liberia and Mozambique are among the highest scorers on the Hidden Hunger Alphabetize in pre-school children). So, if we want to exist adequately nourished while preserving global state diversity, we demand to find a compromise.

Are there whatever higher-income countries which manage to achieve practiced health with low-to-moderate country requirements? Japan offers one case: despite loftier income levels, anybody could adopt the average Japanese nutrition and we'd nevertheless be able to spare some current agricultural land. However, Nihon has ane of the highest rates of seafood consumption in the world—global adoption of such a diet may simply substitute land resource pressures to our oceans.

Determinants of a land-intensive diet

Nonetheless, at that place are still big differences in dietary land requirements betwixt countries of a similar income-level. Why, for example, is the requirement for a New Zealander more than double that of a UK citizen, despite them having similar levels of prosperity?

Alexander et al. (2016) highlight that the types of foods we swallow have a much stronger impact on land use than the quantity alone. The land requirements of different diets tend to be most strongly correlated to a country's level of per capita meat consumption—and most notably that of ruminants (beef and mutton).two , 3

In the chart we run across the HALF index (on the y-axis) plotted confronting the average per capita consumption of beef (on the x-centrality). Here nosotros encounter a very strong human relationship: the more than beef we swallow, the higher our state use requirement. Such strong correlations are not seen for other meat types, such as pig meat (where in that location is no clear human relationship between intake and land requirements). The key outlier on this plot is New Zealand—its population besides has a strong preference for lamb/mutton, which requires a similar amount of land per kilogram of meat as beef does.

We see that countries with depression land requirements have very low levels of beef consumption—near all countries which fall below the 50 pct habitable land mark have per capita consumption levels well below 10 kilograms per year.

Could productivity gains give united states more than land?

The global-diet thought experiment we considered in a higher place has one of import drawback: it is demand rather than supply-oriented, and does not account for the possibility of spared land from productivity gains. Yields have increased significantly over the past 50 years, assuasive us to 'spare' country which would have otherwise been converted to agriculture. Could connected increases in yield spare more land for usa to utilise for agriculture?

There are a couple of considerations to take into account. Firstly, although we expect yields to increment—especially in countries with stiff economic growth—global population is likewise growing; by 2050 we volition have a further 2-3 billion people to feed. In society to spare land from crop product, yields therefore need to increment at a faster rate than population growth. This is non implausible: most countries (with the exception of many in Sub-Saharan Africa) have managed to increase cereal product at a faster rate than population in recent decades. However, some of the potential yield gains in the decades to follow will be offset by a growing population.

The second consideration to notation is that, every bit nosotros have explored above, the dominant contributor to dietary land requirements is livestock rather than crops. Although productivity in livestock farming has increased over the last 50 years, this change has been more small than gains in crops yields; the meat yield per cattle has increased by approximately i-third since 1961, which is significantly lower than improvements in cereal yields, which accept grown more than than five-fold beyond many countries. This increase in animal productivity has likewise been strongly first past global meat production which has more quadrupled over the same period.

So whilst productivity gains—both in crop and livestock production—could possibly give us more land to utilize for agronomics, population increase and biophysical limits mean such increases are unlikely to change the global map of habitable land requirements.

Private action to reduce land use requirements

Looking alee, what can nosotros do as individuals to reduce the land requirements of our diets? If we are to allow room for anybody in the earth to accomplish diverse, nutritious diets whilst also reducing agricultural pressures, it'south articulate that high-income countries will have to adjust their average diets in order to reduce their relative impact.

How do we do this? Arguably the highest-impact change we can make to our diets is to reduce our meat intake—especially that of beefiness or mutton. In the nautical chart below nosotros see the relative land requirements per gram of protein across a range of food commodities.4

We see that even relative to other meat products, the land requirements of beefiness and mutton tin be a magnitude higher per gram of poly peptide. Therefore, even substituting beef with craven would reduce the land footprint of your dietary meat source 10 to 15-fold.

At national levels, this would crave a large shift in dietary preferences away from loftier-impact meat products. To reach a beefiness/mutton intake of 10 kilograms per year, countries such as the U.s.a., Brazil or Australia would accept to reduce consumption by more than two-thirds; a major transition in dietary habits. In that location are, however, some indications of positive change: beef consumption beyond a number of high-income countries appears to have peaked, with many now following a downward (admitting slow) trend.

crichtonhatichoode.blogspot.com

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/agricultural-land-by-global-diets

Post a Comment for "How Many Acres Is Required to Raise a Pound of Beef"