A Rare Case of Colon Cancer With Metastases to the Bone With Review of the Literature And Rodrigues

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Does colon cancer ever metastasize to bone offset? a temporal assay of colorectal cancer progression

BMC Cancer volume 9, Commodity number:274 (2009) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

It is well recognized that colorectal cancer does not oft metastasize to bone. The aim of this retrospective study was to establish whether colorectal cancer ever bypasses other organs and metastasizes direct to bone and whether the presence of lung lesions is superior to liver as a better predictor of the likelihood and timing of os metastasis.

Methods

Nosotros performed a retrospective assay on patients with a clinical diagnosis of colon cancer referred for staging using whole-body 18F-FDG PET and CT or PET/CT. We combined PET and CT reports from 252 individuals with information concerning patient history, other imaging modalities, and treatments to analyze disease progression.

Results

No patient had isolated osseous metastasis at the fourth dimension of diagnosis, and none developed isolated bone metastasis without other organ involvement during our survey period. It took significantly longer for colorectal cancer patients to develop metastasis to the lungs (23.3 months) or to bone (21.2 months) than to the liver (9.8 months). Conclusion: Metastasis only to bone without other organ interest in colorectal cancer patients is extremely rare, perhaps more than rare than nosotros previously thought. Our findings suggest that resistant metastasis to the lungs predicts potential disease progression to bone in the colorectal cancer population better than liver metastasis does.

Background

Colorectal cancer remains the third most common cancer among adult men and women in the United States and the third most common crusade of death from cancer [one, ii]. It is well accepted that colorectal cancers metastasize to the liver and lungs more frequently than to os or other organs [2]. This pattern of interest has been attributed both to the blueprint of blood period from the colon to the portal system and to molecular signal proteins inherent to the microcosm of each organ system; even so; whether one component is more important than the other is still under debate [2–4]. Many studies have focused on characterizing which organ systems are near affected by colorectal cancer metastasis; withal, it remains unclear whether there is a specific temporal pattern for metastasis.

If isolated bone metastasis is truly rare in colorectal cancer patients, then clinicians can exist very conservative in evaluating a suspected bone lesion without other organ involvement. Because bone metastasis often indicates the terminal phase of colon cancer, clinicians should be more vigilant nearly possible bone metastasis in colorectal cancer patients with lung metastasis.

The aim of this retrospective report was to establish whether colorectal cancer can bypass other organs and metastasize directly to bone and whether lung metastasis is better than liver metastasis for predicting whether and when bone involvement develops. In addition to determining which other metastasis more effectively predicts impending bone lesions, we determine whether the presence of liver or lung lesions correlates with the increased likelihood and the timing of bone metastasis.

Methods

Nosotros submitted an awarding to The University of Texas Medical School at Houston Institutional Review Board, which granted us permission to access patient records for this study from 3 outlying medical facilities. Nosotros acquired information retrospectively and gave patient a random numerical lawmaking for identification purposes.

We searched the serial imaging reports of all patients referred to these outlying medical facilities from January 2000 to December 2008 with F-18-flurodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET in correlation with a recent CT or PET/CT and institute those with a clinical diagnosis of colon cancer. We analyzed a full of 703 reports from colon cancer patients (an average of 3.04 reports per patient). We attempted to take PET and CT scans for all patients with a diagnosis of colon cancer for staging/restaging or treatment monitoring. Some colon cancer patients never had PET/CT scans because of variable clinical problems or insurance status and these patients were not included in this study. Stage of the patients ranged from phase I to stage IV. We excluded patients if they had a second principal cancer. Thus, we included 252 patients with a primary diagnosis of colorectal cancer in this retrospective study. This group contained 122 female patients (48.4%) and 130 male patients (51.vi%).

We included all 252 individuals when we determined organ involvement. However, when calculating the time and sequence of metastatic spread, we found that 21 of the 252 patients had presented solely for initial staging and excluded them from that assay. The 231 individuals had a known date of initial diagnosis and the fourth dimension of new metastasis noted in the serial imaging reports during the investigation. Of the 102 patients with organ metastasis, 71 patients received further chemotherapy; 12 patients received combined chemotherapy and surgery; 16 patients received combined chemotherapy and radiations therapy; 2 patients received surgery only; and 5 patients received no therapy. The status of treatment for v patients later metastasis was uncertain. 19 patients developed new organ metastasis merely at the finish of our survey periods. Time to development of metastatic disease was defined every bit time from initial diagnosis to the appearance of metastasis in imaging studies.

To minimize the impact of institutional variability, we included imaging studies only if they had been read originally past i of 3 certified nuclear medicine radiologists.

Prototype Interpretation

Board-certified nuclear medicine radiologists initially interpreted the imaging studies by using a GE Advanced Workstation for PET/CT cases or MIM vista fusion program (MIM vista Corp) to analyze PET and CT images before we conceived and conducted this study. Another individual later on extracted information from the reports to include in this study. Metastases to the liver, lungs, and bone were recorded. Because PET has low sensitivity for detecting brain tumors, nosotros did not assess brain metastases. Illness progression was documented when an imaging report showed involvement of a new organ arrangement. If a metastasis resolved after the patient received therapy, the metastasis was still recorded based on the date on which it was commencement identified by imaging.

Ane certified nuclear medicine radiologist reevaluated any inconclusive or contradictory information and confirmed the findings if lesions were visible on subsequent imaging studies or if other imaging modalities confirmed the presence of the lesions. We excluded imaging studies if nosotros could non detect a subsequent imaging report to confirm the lesion.

Statistics

Information were expressed equally hateful ± SD. We used the Microsoft Excel 2003 to calculate the conviction intervals. We determined the statistical significance of differences by using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test and considered P values of less than 0.05 to exist statistically pregnant. Because we focused on the temporal blueprint of the onset time of organ metastasis, we did not perform Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for this report.

Results

Of the 252 patients, 55 (22%) received adjuvant local radiation therapy and 195 (77%) underwent adjuvant chemotherapy in addition to the surgical removal of the primary tumor. The mean patient age was 64.ii years at the time of initial diagnosis, with a standard deviation of xi years. The average follow-up menses after diagnosis was 38 months, and 21 of 252 patients (viii.3%) presented solely for initial staging. Tabular array 1 shows stages and therapy.

Organ involvement in the 252 patients comprised metastases to the liver, lung, and bone. In that location was picayune divergence between male and female patients (data not shown). Overall, 102 of the 252 patients (xl%) had organ metastasis.

Lx-three of the 252 subjects (25%) developed lung metastasis, and 75 of 252 individuals (30%) developed liver metastasis. Only 4 of 63 patients (6.iii%) with lung metastases had them at diagnosis, whereas 21 of the 75 (28%) with liver metastasis did (Table two). Twenty-iii of the 63 lung metastasis patients (36.v%) developed lung metastasis starting time without other organ involvement, whereas 48 of 75 patients (64%) had colorectal cancer that metastasized to the liver without showtime involving other organs. Xl-nine of the 63 lung metastasis patients (77.8%) had concurrent other metastases, whereas 42 of the 75 liver metastasis patients (56%) did. Fourteen of the 63 subjects (22%) with lung metastasis remained gratuitous of metastasis to other organs during follow-upwards, whereas 33 of the 75 patients (44%) with liver metastasis did. Merely ii individuals developed lung metastasis earlier subsequent liver metastasis, whereas others showed lung infiltration more slowly, years later on initial diagnosis.

Analysis of metastasis to os showed 14 of the 252 individuals (v.v%) had bone lesions and no individuals had metastasis but to bone at the time of diagnosis. No patient developed bone metastasis without liver and/or lung metastasis. One individual presented with os lesions at the time of diagnosis; however, liver metastasis was likewise present.

Of the 14 patients with lesions to bone, viii (57%) had both liver and os involvement, whereas 10 (71%) had lung metastasis. Fifty-3 of the 63 patients (84%) with lung lesions remained free of metastasis to bone during follow-upwardly. Similarly, 63 of the 75 patients (84%) with liver metastasis also remained gratis of metastasis to os during follow-up.

The average time from initial diagnosis to detection of metastatic affliction was 9.8 months (± xiv.9, confidence interval [CI] 6.2–13.three) for liver involvement, significantly shorter than the average times of 23.3 months (± 25.three, CI 16.4–30.1) to detect lung metastasis and 21.2 months (± 18.5, CI 11.2–31.iii) to discover metastasis to bone (Table 3), P < 0.05. The average time for colon cancer to metastasize from the liver to bone was 8.3 months (± xiii.4, CI 0.6–xv.ix), whereas the fourth dimension to metastasize from lung to bone was 3.iii months (± 4.2, CI 0.vii–5.9). Withal, this deviation is non significant because of the pocket-sized sample size. Among the 8 patients who exhibited metastases to liver, lungs, and os, the average time for the cancer to metastasize from the liver to bone was also longer than the time for the cancer to metastasize from the lung to bone (6.0 months ± 11.1 versus four.3 months ± 6.1). However, the results are not statistically significant. On average, interest was detected in all iii organs within 30 months of the original diagnosis of colon cancer.

Of the 14 patients with metastasis to bone, 2 were still alive, 2 were lost to follow-upwardly, and 8 were dead past the finish of this study. The average time from when bone involvement was detected until the patient died was 15.nine months (± thirteen.two, CI 6.7–25.1), and the average lifespan of patients with os metastasis afterward initial diagnosis of colorectal cancer was 42.4 months (± 18.ane, CI 29.8–54.ix).

Discussion

Analysis of Involvement in Bone

This study adamant that despite individual variance in the degree and society of organ interest among patients with colorectal cancer, a general temporal pattern does exist. Malignancies never spread primarily to bone. This is a characteristic item to colorectal cancer equally os metastasis is far more frequent in the other leading cancer types. Although clinicians nevertheless cannot agree on the prevalence of breast, lung, and prostate cancers metastasis only to bone is a mutual occurrence in these cancers [5]. One study even postulated that as many as seventy% of patients with stage IV breast cancer have bone involvement [6]. By contrast, cancer typically metastasizes to bone in less than 10% of colorectal cancer patients [7]. This suggests that colon cancer behaves differently with respect to bone metastasis compared with other cancers.

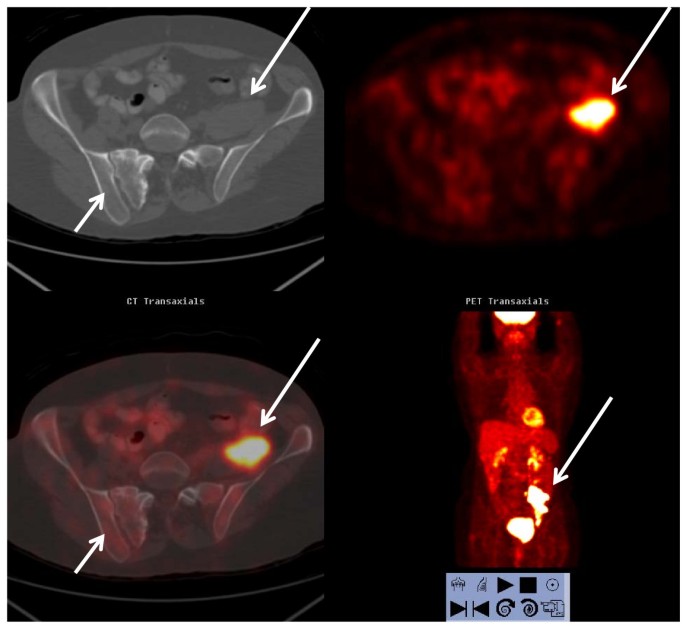

Our report results also confirm this unique behavior. No cancer metastasized to bone without first metastasizing to the liver or lung in our study. This finding contrasts with a previous study on os metastasis in colorectal cancer patients by Kanthan et al [8] in which ane.1% of colorectal cancer population developed isolated metastasis. Nonetheless, that study used os scans and obviously radiography to notice lesions, and both methods have low specificity that may overestimate the actual incidence of bone metastasis. This possibility was demonstrated during our data acquisition, when PET/CT disproved the findings of a positive bone scan in the pelvis, by demonstrating that in that location was no indication of bone metastasis on either PET or CT browse. Patient's remote history of pelvic fracture probably led to the false positive result of the bone scan (Figures 1 and two). Another instance that originally appeared equally os metastasis to the pelvis on a os scan was identified equally local/direct tumor invasion into the sacrum on the PET and CT scans (data not shown).

Bone browse posterior view of a 54-year-old adult female with a ii-twelvemonth history of recurrent colon cancer revealed a focal tracer uptake in the right sacroiliac joint area suggesting possible bone metastasis.

FDG PET/CT scan of the same patient in Effigy one revealed no focally increased FDG uptake or suspicious abnormalities to bone on the CT of the correct sacroiliac area to stand for the bone scan findings (curt arrows). The patient's history of pelvic fracture probably explained the focal tracer uptake in bone scan. The recurrent colon cancer in the left pelvis observed past both PET and CT scans is marked by the long arrows.

Information technology is also likely that the college sensitivity and specificity of PET and CT for detecting early metastasis in liver and lung compared with traditional radiography may account for the strong correlation among lesions to the liver, lung, and bone in our written report. Perchance, concurrent involvement of other organs did exist but went undetected in the patients who had only bone lesions in the Kanthan et al report [8]. However, confirming whether the consummate absence of true isolated os metastasis is characteristic of colorectal cancer will require a larger study population.

This report sought to identify whether disease progression to the lungs could predict metastasis to bone. Although lung lesions are of detail interest equally a precursor of futurity os metastasis as evidenced by the brusque time span from lung metastasis to bone involvement, the lesions in bone ever appear afterwards metastasis to liver, lung, or (in a large pct) both. As the average 5-yr survival charge per unit of colon cancer patients with metastasis to os continues to be 8.1% [9], and on average, 67% of those who developed os involvement during this survey were dead 16 months afterwards detection of os metastasis, the importance of recognizing disease progression and potential significance of bone metastasis cannot exist overemphasized.

Disease Progression

The findings in this report regarding colon cancer metastasis to the bone and lungs correlate with results in the current literature. Our findings of lung metastasis in 25% of patients and bone metastasis in v.five% of patients agree with the results from other studies [2, viii]. Equally reported in the literature that colorectal cancer metastasizes first to the liver or lungs, which both incorporate dense capillary beds that can trap tumor cells and seed them into these organs [3]. The environment of a specific organ and its influence on tumor cell adhesion can also contribute to the efficacy of tumor spread, which occurs in colorectal cancer patients most oft in the liver and lungs [2, iii].

Withal, the 30% incidence of liver metastasis in our written report is much lower than the incidence of liver metastasis in before studies, which reported liver involvement in 70–83% of patients [ii, 8]. The lower incidence of liver lesions detected in this study may be due to patient option, because clinicians had resected the primary tumors in well-nigh of our patients and were monitoring them to evaluate possible recurrence during the investigation. During the report period, 44% of those who developed liver metastasis remained free of other organ metastasis, and 84% had liver lesions that never progressed to os.

The percentage of metastatic lung interest in our report correlates with that reported in the literature. Withal, unlike people with liver lesions, 78% of people with lung lesions showed concurrent disease involvement in other organs. When combined with the temporal difference between the time from liver metastasis to os metastasis and the time from lung metastasis to os metastasis, this finding suggests that lung metastasis indicates refractory, potentially serious disease more precisely than liver metastasis does. Near lung and liver metastases that we observed consisted of multiple lesions. Withal, solitary lesion occurred more frequently in the liver than that in the lung.

Although this study attempted to uncover the relationship between the blueprint of disease progression and the development of bone metastasis, the resulting subpopulation of patients with metastasis to bone was small, and near had diffuse involvement of multiple organs at the same time point. Thus, farther studies with a larger patient population with more frequent imaging studies are necessary to ascertain whether the order of organ involvement has any touch on the evolution of os metastasis.

Lymphatic spread and local recurrence were excluded from analysis in this report because almost patients had undergone local resection with local lymph node dissection before their staging piece of work-up. Further investigation of the possible relationship between the nodal spread of disease, including local or distant nodal metastasis and metastasis to bone in a different patient population setting, would exist interesting. After cancer cells break through the defense barrier of the lymphatic system, particularly those lymph nodes outside the portal system, the cancer may metastasize more readily to the lungs and bone. We did non analyze brain metastasis because of the low sensitivity of PET for brain tumor detection and our PET/CT imaging protocol does non include the brain.

Strengths

A strength of this study is that it included a systematic approach to evaluate disease progression. Using the files of 3 nuclear medicine radiologists facilitated the creation of a big database that spanned institutions, widened demographics, and maintained quality and consistency in the imaging reports.

In addition, unlike most studies that have characterized colorectal cancer metastasis, we used PET and CT, which are newer and more sensitive tools to detect colon cancer metastasis, rather than less precise methods similar traditional radiography or os scintigraphy [8]. Our results are therefore a straight reflection of what diagnosticians can expect to see when staging a colorectal cancer patient using electric current engineering science.

Drawbacks

A major limitation of this study is the retrospective nature. We obtained the imaging studies during staging and subsequent follow-up by using a combination of PET with correlation of a contempo CT and PET/CT. In addition, the imaging modality at each time point varied among patients and we only followed the patients during the imaging periods because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Most of the patients from the 3 outlying medical facilities experienced surgical resection of the main tumor along with removal of neighboring lymph nodes before they had a detailed staging work-up. This patient population therefore may not be representative of full general colorectal patients.

Conclusion

The primary implication of this study for clinicians is that if a colorectal cancer patient has no sign of disease involvement in the liver or lungs, evaluation of a suspicious os lesion should not be aggressive, simply should obtain more than noninvasive data from other diagnostic modalities or follow-up.

Lung metastasis indicates the potential for cancer to metastasize to bone in the colorectal cancer population better than liver metastasis does.

References

-

Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, et al: Cancer Statistics. CA A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2005, 55: 10-30. 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10.

-

Schluter K, Gassmann P, Enns A, et al: Organ-Specific Metastatic Tumor Cell Adhesion and Extravasation of Colon Carcinoma Cells with Different Metastatic Potential. The American Journal of Pathology. 2006, 169 (Sept): 1064-1073. ten.2353/ajpath.2006.050566.

-

Chambers A, Groom A, MacDonald I: Dissemination and Growth of Cancer Cells in Metastatic Sites. Nature. 2002, two (Baronial): 563-672.

-

Kuo T, Kubota T, Watanabe M, et al: Liver colonization competence governs colon cancer metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995, 92 (Dec): 12085-12089. 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12085.

-

Mundy G: Metastasis to Bone: Causes, Consequences and Theraputic Opportunities. Cancer. 2002, ii (Aug): 584-593.

-

Narisawa S: Understanding Breast Cancer Prison cell Metastasis to Bone. American Association for Cancer Research. 2001, 42-

-

Katoh M, Unakami M, Hara M, Fukuchi Due south: Bone Metastasis for Colorectal Cancer in Autopsy Cases. Journal of Gastroenterology. 1995, thirty: 615-618. 10.1007/BF02367787.

-

Kathan R, Loewy J, Kanthan South: Skeletal Metastasis in Colorectal Carcinomas: a Saskatchewan Profile. Diseases of Colon and Rectum. 1999, 42 (12): 1592-1597. 10.1007/BF02236213.

-

O'Connell J, Maggard Yard, Ko C: Colon Cancer Survival Rates with the New American Articulation Committee on Cancer Sixth Edition Staging. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004, 96 (19): 1420-1425.

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this newspaper can exist accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/nine/274/prepub

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was edited by Tegra Rosera, MA, MS, and Maureen Goode, PhD, ELS, of The University of Texas Health Science Centre at Houston Heart for Clinical and Translational Sciences (supported by National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Scientific discipline Award UL1 RR024148).

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

DQW designed the concept of this report and participated in manuscript writing. ESR participated in its design, collected the data and drafted the manuscript. DTZ participated in the study design, collected the data, and revised the manuscript. BJB, UAJ, and IWG provided the study material, gave authoritative support, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and canonical the concluding manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is published nether license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roth, E.Due south., Fetzer, D.T., Barron, B.J. et al. Does colon cancer always metastasize to os first? a temporal analysis of colorectal cancer progression. BMC Cancer 9, 274 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-9-274

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/1471-2407-9-274

Keywords

- Colorectal Cancer

- Liver Metastasis

- Bone Metastasis

- Lung Metastasis

- Colorectal Cancer Patient

crichtonhatichoode.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2407-9-274

Post a Comment for "A Rare Case of Colon Cancer With Metastases to the Bone With Review of the Literature And Rodrigues"